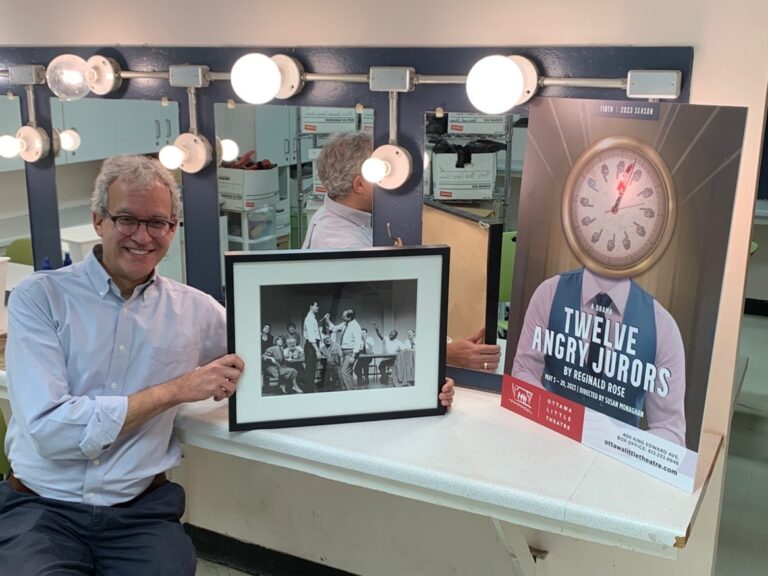

Old School Chums: An Interview with Twelve Angry Jurors’ Lawrence Aronovitch

By Lawrence Aronovitch and Albert Lightstone

Lawrence and I have been friends since nursery school in Montreal back in 1966. We attended the same small elementary and high schools and even travelled on a 3 ½ month summer school trip together to Israel. We were great mates and like the nerdy main character in the TV show the Goldbergs, tried our hand at movie making with a super 8mm. After graduating high school Lawrence went off to Harvard University and later started his career in the U.S. space program. Yes, he’s a space cadet. This interview was a lot of fun for me (and I hope for him as well).

Let’s start this interview off with a bang (no pun intended). What’s the story about you working for the U.S. space program?

Space came first – I began to work in the space program in the U.S. after university. But I was always interested in theatre as well. I suppose it all goes back to when you and I were growing up together in Montreal and we’d be watching Star Trek – the original version, with Montreal’s own William Shatner. Do you remember how we got together with some classmates to make a Star Trek movie together? You played Dr. McCoy, as I recall. Well, that experience clearly inspired me to pursue dual careers in space and the theatre!

How did you go from outer space to the theatre? It does not seem to be a straight line trajectory (again, the space flight reference).

It’s a pretty straight line when you factor in non-Euclidean geometry and Einstein’s special theory of relativity from a quantum mechanical perspective. On a more serious note, I would argue that space exploration and the theatre are very closely related, as are all the sciences and the arts, actually. They are both concerned with trying to understand the universe. Trying to understand pebbles on the moon, trying to understand strands of jealousy in romantic relationships – not such different pursuits, really, in my view, though I suppose they draw on different parts of the brain.

What have you published as a playwright recently?

When you’re a playwright, publishing isn’t actually a priority. Who reads plays? Outside of high school English class, it’s generally actors, directors, and producers who like to read plays. That’s one of the aspects of playwriting that I find so interesting. My conversation with a theatre audience is indirect, because when they watch the story I’m telling unfold, they’re seeing it interpreted through the artistry of the actors, the directors, the lighting and sound and costume designers – all the amazing people at OLT, for example, who bring the work to life. I might create the recipe and the audience might eat the meal, but there’s a lot of talented artists involved in getting from the one to the other.

What inspires you to write?

People. People are endlessly fascinating. I might be at the bar here at OLT, waiting to get a drink, and I overhear a bit of someone’s conversation. Oh, that’s interesting, I think to myself. I wonder what their story is. And the wheels begin to turn and soon I have a story to tell. So if you notice me nearby, you might want to watch what you say out loud.

Do you have a certain goal per year i.e. a number of scripts?

Nope. This is definitely a calling in which quality matters more than quantity.

Are any of your shows currently on or in production?

My most recent show was produced down the street at Arts Court earlier this year. It was a one-man show about the poet W.H. Auden. I am currently working on a new script about two brothers. It’s in development, which means I am working with a talented group of actors to get the script into shape and with luck it will be produced next year.

What would be your most famous produced play?

I’m not sure which might be the most famous, but one that’s received a lot of attention is called Finishing the Suit, which tells the story of a tailor who made suits for the Duke of Windsor and then went on to design costumes on Broadway.

What is your most personally satisfying work?

Hm, how do I choose which of my children I love best? I suppose the Auden play is on my mind lately because of the recent production at Arts Court. In addition to telling a theatrical story, it’s also a call to arms about the importance in our lives of poetry in particular and the arts in general. It’s about what makes us human.

What is your biggest challenge when writing a play?

These days, I think the biggest challenge for playwrights – and for others working in the theatre – is the environment we find ourselves in since the pandemic. There’s a great thirst for live theatre, but theatre companies are dealing with actors and backstage crew members who get ill and audience members who may be reluctant to return to an auditorium full of strangers. In the meantime, the resources for producing theatre are not as plentiful as they’ve been in the past, which makes producing a show a challenge. For playwrights creating new work, which by definition is risky – what if it’s not a very good play? – there’s the additional challenge of persuading producers to try something new rather than to rely on old favourites that have already proven themselves to audiences.

Is playwriting your full time job? If not, what is?

I do have a few other things I do to help pay the rent, and as a parent I have another full time job, but playwriting is certainly a full time job in the sense that it is constantly on my mind.

You grew up in Montreal, ended up in Ottawa, then Toronto and back to Ottawa. What’s the background story?

You missed a few stops along the way. After you and I finished high school in Montreal I moved to Boston for university and for work in the space program before coming to Ottawa. I also lived on the west coast for many years, as well as in Ireland for a bit. Generally, all those moves were related to school or work, but in recent years it’s involved a fair bit of theatre too. I worked on two plays while living in Ireland, for example, and given how important theatre has been to Irish cultural identity, it’s no surprise that I found it to be an exceptionally welcoming place to be a playwright. Finishing the Suit, for example, was inspired by a tailor I met in Dublin when I was looking for someone to make the suits my husband and I wore at our wedding.

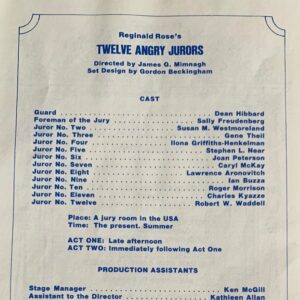

When did you first get involved with the Ottawa Little Theatre? What was the production? What else have you done at the theatre?

I had been working in the space program in the Boston area for several years when the Canadian government decided in the late 1980s to start its own space agency. I knew some of the people involved, and they invited me to join them, which is how I ended up in Ottawa. It was a dream job, but I thought it might be nice to get involved with something outside of work. I saw an ad in the Ottawa Citizen for an audition at OLT – this is how these things were done before the internet! – and so I dropped by on a Sunday afternoon to try out for Twelve Angry Jurors. I had the good fortune to be offered a role as Juror #8 and that was the start of a beautiful relationship. Over the next many years, I was able to act in several shows – including two different productions of The Importance of Being Earnest – as well as volunteer in various other capacities, including some time on the board of directors.

How has the theatre changed over the years?

I’m sure it’s changed in any number of superficial ways – for example, there’s probably more technology lurking behind today’s productions than was used to go to the moon half a century ago. But I think the fundamentals of what makes OLT so special are timeless: a desire – a need, really – to share in the magic of live theatre, whether as a performer, a designer, or an audience member. I remember dropping in at an audition after moving back to Ottawa from Vancouver and being warmly welcomed home by old friends – it was a delight to glide back into the OLT routine (and to be offered a part in a classic play, The Lion in Winter.)

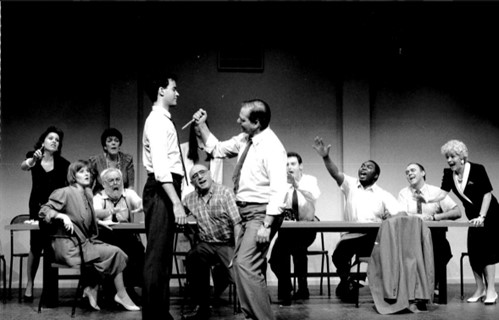

What are your memories from your first production of OLT’s Twelve Angry Jurors? How has it changed or improved ?

The play is an ensemble piece, with all twelve characters on stage throughout the performance. For the actors, this meant we were always together throughout the rehearsal period, and this afforded us the opportunity to become quite close. After rehearsals we would all retire to Nate’s Deli on Rideau Street to get a late-night snack and gossip about the theatre. I met some of my dearest OLT friends during that show, and I hope that the current ensemble has enjoyed as warm an experience as I did.

The picture you are holding is of you being stabbed. What’s going on there?

I can only assume that this was a gentle reminder of what would happen to me if I forgot my lines.

Is it weird to be coming back as an older and wiser judge (albeit as a voice only)?

It’s a delight to have the opportunity to be a link between the 1990 production and today’s team. One of OLT’s strengths is its deep roots going back over a century, so it’s very much in the tradition of the institution, I think, to span the generations in this way. The only part that’s at all weird is that I didn’t actually get to interact with the cast. I recorded the judge’s speech in solitude earlier this year, just me, the director, and the sound designer, all huddled in the wardrobe department in the basement. (All those costumes make for an excellent sound environment for recording, it seems.)

Your husband is a director. What is he currently working on? Do you collaborate at all together?

He works primarily in French and is currently helping a Francophone playwright with the development of a new script. As a professor at the University of Ottawa, he is also training the next generation of directors who will work in both French and English across Canada. He has directed three of my plays to date, including the recent Auden production at Arts Court.

How old is your daughter now? Has she inherited any of her parent’s theatrical talent?

Our daughter is turning 9 and yes, in spite of our heartfelt protests, she shows an alarming flair for drama. Fortunately, she is also interested in soccer, geology, comic books and other pursuits as well.

Do you have any advice for any of the readers who are aspiring playwrights?

In my experience, it’s important for you to have a story that you feel has to be told. Otherwise, why go to the trouble of writing the play? It’s also important that you feel that the best way to tell that story is theatrically – live, on stage, rather than in the reader’s imagination, as in a novel, or on screen as in TV or film. Those are the fundamentals. As to the mechanics of writing the play, my advice would be to see as much theatre as you can to discover what appeals to you, and to read the scripts of plays that you like to learn how other playwrights have gone about their craft. Once you’ve done these things, then you need to sit down and write. And then re-write. And re-write some more. They say a script isn’t really finished until the curtain goes up on opening night.